This article deals with social movements that originated from the commons. It attempts to analyse the kind of contribution that can be made to the process of creating an emancipatory, participatory, and just governance form of politics developed for defending mutually beneficial, commonly used and shared resources, and values and opportunities of urban life. With this in mind, an introduction will be provided into the concept, content, and narrative of the term ‘commons’ that has recently been added to the Turkish language; next the situation in which these resources and values are included will be presented; then the movements that have arisen from urban commons will be described both quantitatively and qualitatively; and lastly the issues arising from consociational and participatory movements, initiatives, and experiences desired for the urban commons and the opportunities they offer will be elaborated.

Largely due to political, legal, and managerial policies recently adopted, the distinction between urban and rural has become ambiguous as the gap between quality and quantity of urban and rural has widened, and negative developments on both sides have begun to affect each other. Therefore, this article analyzes the commons by encompassing ecological resources and urban spaces together.

I. A new concept: The commons

It is not easy to immediately grasp the full content of this new concept of the English term ‘commons’, recently translated into Turkish as ‘müşterekler’.[1] The underlying reason that makes the meaning of this word quite ambiguous is that it is such a new concept that has only recently come into use and there are also some morphological difficulties as it is derived from an old word ‘iştirak’. In addition, semantically it has a rather multi-layered content and this obstructs the association of ideas.

The word commons, which refers to shared places, communal property, or things that cannot be appropriated, refers to a set of three core meanings: firstly, natural resources such as air, water, soil, forests, and seeds; secondly urban areas such as roads, streets, parks, squares, and coasts; and lastly, social and cultural values such as science, internet, arts, languages, and traditions.[2] It is, therefore, quite natural for such a concept that sometimes touches on tangible assets and sometimes intellectual and social assets not to have an exact equivalent in Turkish.

Taking into consideration the economic, legal, and geographical conditions of Turkey and words that may be deemed similar in Turkish, we can see that it is not so easy to grasp the exact meaning of the term ‘commons’ or even to remember it for that matter. It is a concept that sometimes refers to ‘concrete’ concepts, such as pastures, coasts, and city centres, and ‘abstract’ notions, such as social values, traditions, and tales. Hence, it can be said that the most important attribute of the resources and values that this term embodies is that they are beyond market rules and have no monetary value or price whatsoever (Bollier, 2014). In a way, the commons can also be considered as goods, spaces, and social relations with which the left wing defends principles such as “justice, sharing, solidarity” against those of the right, i.e., “family, religion, nation” (Haiven, 2018: 35).

The song below, For Free, which was written by Orhan Veli Kanık and set to music by Özdemir Erdoğan in 1949, actually refers to today’s notion of the commons.

For Free

We are living for free;

The air’s for free, the clouds are for free,

Hills and creeks are for free.

Rain and mud are for free.

The outside of cars,

The foyers of cinemas,

Shop-windows are for free.

Not bread and cheese,

but hard water is for free.

Freedom costs you your head;

Slavery is free;

We are living for free.

For free.

by Orhan Veli

Even though the term ‘commons’ is at first not an easy one to grasp and the whole concept appears foreign to Turkish literature, the issues it refers to and the problems it focuses on are not that new at all. City and environment-oriented developments such as the loss of forests, the deterioration of protected areas, the collapse of agriculture, GMO foods, the plunder of coastlines, zoning of lands for construction, parking problems, and urban transformation are just some of the issues that belong in the realm of this term.

As the name implies, ‘the commons’ refers to, for example, ‘the whole of a community, or common meals, etc.’, as well as to non-privileged masses, public places, sharing, and cooperation. We can say that this term, which shares the same root as other words such as community, communication, and commonwealth (Haiven, 2018: 79), in a way includes spaces, resources, and social relations that can be excluded from the influence of the capitalist system. For this reason, these areas, that is to say the commons, are, of course, going to be the first places for governments that are seeking to enlarge their economy to attempt to possess in order to consolidate more power, increase their oppression, and support their cronies.

Behind the conflicts and movements initiated by the commons are the common values and natural living environments that people, animals, and other living things encompass. Pastures and natural resources such as forests, shores, and seas can host large masses of people and other creatures. What’s more, the community can freely benefit from many aspects of these areas without having to resort to the monetary system. These areas can further be used to accommodate social demonstrations and political movements, for example in parks, streets, squares, or, as we see in the case of the internet, provide communication and thus the necessary conditions for solidarity. Additionally, they can even play a vital role in promoting awareness in music, art, and education. In other words, the commons carry a wide range of functions involving the establishment of life, maintenance of livelihoods, sustainability of the economy, and the development of culture.

These three main areas, i.e., common natural resources, urban elements, and social-cultural values, are all vital for the capitalist system in one way or another. With the more common use of the word commons, common spaces and common properties have begun to have a much stronger voice as these three values are the mainstays of capitalism and capital accumulation.

As should be clear from the above description, each and every area, environment, value, and cultural asset evaluated within the concept of the commons is regarded as a resource for capitalism. Everything utilized and shared by the common space described by the word ‘commons’ is of pivotal importance to the existing system, in that they could also be seen as a great threat to the existing system of values and form of social relations. With the discourse that says “rivers, which do not belong to one single person or rather belong to everyone, flow for no reason and are therefore pretty much wasted, and that public squares are not safe anymore or that the urban neighbourhoods are corrupted by crime”, it has been possible to introduce necessary regulations to appropriate these values for private property (Fırat, 2011; 2012). In a way, the commons actually represent areas that can be excluded from traditional and ‘modern enclosure movements’, i.e., the control of the sovereign economic system and capital. Hence, by their very nature, these areas can certainly be expected to be a target of capital and integrated within the capitalist system.

Generally speaking, the commons, that go unnoticed under normal circumstances, start to gain importance and take on vital functions, especially in periods of crisis, since they are considered naturally existing, and there is simply no cost in their utilization phase. Some examples of this are the use of natural resources in order to sustain daily life during economic depression, or in the development of alternative forms of production and consumption (such as barter markets and food cooperatives) to the existing economic system, as well as the gathering of people in the form of urban commons or via the internet amidst political crises (McGuirk, J., 2015). Calling the communal tent in the park ‘commons’ during the Gezi protest is a good example (Güner, 2014). In a sense, in moments of economic and political crises, commons tend to become a rather vital element for a vast majority of the public. And yet for capitalists and financiers, they are merely seen as an opportunity in terms of ‘primitive accumulation’ in order to strengthen their existence (Caffentzis, Federici, 2015).

Nevertheless, it should not be concluded that the current economic and political structures are based on the immediate destruction of the commons. In the search for ways to make maximum use of these assets and values, which are the mainstay of capital accumulation and economic growth, appropriate methods such as ‘sustainable development’ are devised. A number of mechanisms, such as ‘precautionary principle’, ‘public participation’, and ‘polluter pays’, which are referred in the literature today as the basic principles of environmental management or environmental law, also shed some light on the ways and methods that are in a way capable of protecting the commons. As an extension of the same approach, the process of appropriating, harming, and destroying the commons, which are assumed to be common property or value, is expressed within the concept known as ‘negative externality’ (Walljasper, 2015: 77). This concept, which is used to describe the positive or negative effects of any one activity on others, has particularly stuck in our mind with the example of environmental pollution caused by factories. As regards the commons in Turkey, the concept refers not only to air, water, or environmental issues such as soil pollution but also to the destruction of forests, the deterioration of food, and the difficulties of transportation and climate change. Preparing statutory measures mainly based on intra-system material elements such as legal measures aimed at preventing the negative effects of externalities, for example, additional taxation, compensation, fines, and emission permits, etc., has not actually been effective in compensating for the damage done to the commons.

The distinction between commons and open spaces

It should be noted that some consider commons as something different from a ‘public spaces’ or ‘common property regimes’. Garrett Hardin is a leading pioneer in the formation of the commons literature. In the Tragedy of the Commons, written in 1968, he explained that public spaces and assets would enter into a process of wear and tear after a while, which would lead to their ultimate destruction, as each beneficiary would only be concerned with his own gain. As a precaution, he proposed to either nationalize or privatize these places (Adaman et al., 2017: 15). Elinor Ostrom, who won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2009, has strongly opposed Hardin’s views in her work. Ostrom says that those benefiting from common assets have developed unique methods to prevent uneven and unbalanced use. And she adds that when pressure increases with outsiders and changes in the form of established management begin, problems quite naturally follow (Brent and Sharma, 2015; Akbulut et al., 2015). According to Ostrom, the areas that Hardin mentions should not be regarded as commons but as public spaces with no rules of joint use and with ‘open access regimes’[5] (Angelis and Harvie, 2017: 115). To put it another way, in order for any space, resource or asset to be considered a common, some certain issues need to be clarified such as who is expected to benefit from them and what the rules of use are. What’s more, the type of customs pertaining to their supervision and sustainability should be established.

II. Commons in Turkey

The main reasons why there is a considerable increase in the level of the quantitative and qualitative importance of the commons in Turkey, and also why natural, artificial, or cultural commons have a rather strong place, are that a significant portion of the country’s land is still state-owned (thanks to the manorial system and heritage of Ottoman land law), forests take up a relatively large area, the country is regarded as a transit country in terms of its history, geography, and culture, and finally there is still an ongoing urbanization process. To be more precise, most of the state-owned land reclaimed from migrants who lived in substandard housing (gecekondular) for urban transformation have created many commons-centred problems. In addition, forests have begun to be damaged by the energy and housing sectors, and tourism is having an increasingly negative impact on both culturally and historically rich areas.

It is possible to say that economic policies are typically being developed in such a way that they are likely to result in some loss of or damage to common urban elements and natural resources. This approach, which currently is a priority of the AKP’s energy, transportation, housing, and tourism investments, stems from viewing natural resources such as water, land, and forests as unlimited. In other words, the fact that Turkey is quite a wealthy country in terms of the commons has inevitably led to an overwhelming pressure on them.

The end of the urban-rural divide?

Since the title of this study contains the term ‘urban commons’, you might think that the sole focus will be on common spaces and values within the city. However, over the course of time, the urban-rural distinction has blurred as the distinction between managerial and political differences have gradually become vague and developments in these areas have affected each other in a rather negative fashion. In this regard, it is more meaningful to evaluate the commons in terms of natural resources and urban spaces together.

There is a correlation between the damage and destruction processes of rural and urban, as well as natural and artificial commons. The best example that clearly shows that these two concepts are not really separate from each other is the closure of rural and subnational municipalities in small districts. With the help of legal regulations, the area covered by metropolitan municipalities has been extended to the borders of the city. Consequently, thousands of villages and municipalities have been put under the control of metropolitan areas.

Transferring the management of rural areas over to urban administrations has created the strongest intervention in the commons in recent years. With this legislation, peasants’ common goods, such as water, soil, and pasture, have been appropriated by the metropolitan cities. In this way, the commons that the indigenous populations of the region traditionally used to share have been taken away from them and the administration of them handed over to external central units, often situated many miles away. It is not surprising that these assets are and will be transferred to the use of certain companies. It is possible to say that the abovementioned regulations, which are bound to have considerable legal, administrative, and ecological effects, have planted the first seeds of the centralization of property and the deterioration of natural resources.

The policies that put pressure on both natural and artificial environments seem to accelerate the process of obscuring the distinction between urban and rural commons and, what is worse, they are not the only ones. Large-scale energy, transportation, housing, and tourism developments have not only damaged natural resources, such as water, forests, seas, and coasts, but also forced some of those living in small villages and towns to migrate to the suburbs of metropolitan areas. The last few years have seen extensive damage to olive groves and a rapid increase in the number of coal mines that has led to disastrous landslides. What’s more, villagers have been diagnosed with diseases such as asthma, bronchitis, and cancer, which has led to the evacuation of 48 villages (Eroğlu, 2018).

That such small governmental units begin to lose their power and are threatened with closure can be seen as a step paving the way to the destruction of the commons. In particular, considering the administrative, decentralization, and solidarity regulations of Village Law, it is recognized that the management of each element, from squares to mosques and from forests to wetlands, is, in effect, left to the common will of the people of the village. Hence, it would not be wrong to see villages and similar small emancipatory settlements as some of the examples of the commons.

Examples of commons: Villages and Village Law

The term ‘commons’ includes three sets of meanings: natural, urban and cultural values. It refers to a wide variety of tangible and intangible elements, ranging from unclaimed property to common traditions. It has become a truism to claim that the commons are either directly or indirectly related to innumerable legal regulations. Leaving the basic legislative regulations such as the Penal Code, Environmental Law, Forest Law and Misdemeanour Law aside, it can also be said that the most powerful notion of the commons can be found in the Village Law of 1924. The law clearly states that “the gathering of male and female villagers who have the right to choose the village headman and council of elders is called a village”. Article 15 of the Law states that “most of the village work is carried out through collective participation of all villagers”. Article 2 states that “people who have the right to shared goods such as mosques, schools, pastures, highlands and coppices and who live in nucleated or dispersed settlement patterns with their vineyards, gardens, and farms are the constituents of a village”. These lines refer to both common beneficiaries (shared goods) and collective management (Village Society), as well as solidarity (collective work). Although the rules for sharing of public spaces and the continuation of life with solidarity were established primarily to ensure integrity within the country and to strengthen local governments, in effect the state turned out to be unable to take all of its local services to all corners of the country (Duru, 2013).

The AKP and commons

It has been mentioned that the commons in the urban and environmental areas in particular are important beneficial resources in terms of sustaining economic growth, capital accumulation, and empowering the government. Thus, these areas in countries where there is uncontrolled economic development, such as is the case with Turkey, are under greater threat in that natural commons such as pastures, forests, and water can be appropriated for economic operations without any limitations; urban areas such as roads, squares, and parks can be closed to the public due to political fears; facilities such as the internet and social security can be regulated in accordance with the rules of capitalism; and lastly, art and music activities can be suppressed by oppressive means.

a. In terms of nature and the city

Since the establishment of the AKP, and especially as their effects went wide of the mark regarding the European Union, the first and foremost important negative impact of the economic policies they have pursued has been on the natural, urban, and cultural resources called the commons. The aftermath can be seen in the deterioration, pollution, degradation, and destruction of common resources and values such as forests, parks, squares, and seas which have previously been used as shared public spaces. Another problematic is seen in terms of the use of the commons by the general public in the city. For instance, some regulations oblige individuals to pay for the use of the commons, often restricting or even preventing people from using them. Consequently, with regard to the rights of solidarity, demands for the right of access to the environment, right to the city, housing, transportation, education, and health, all of which are evaluated, have all come to the fore.

It would not be wrong to say that under AKP rule, the overall economy has been built upon the commons, natural and urban in particular. The traces of this approach, known as ‘a construction-based one, rather than production’ can be detected in the construction of apartments, skyscrapers, bridges, and dams, all of which are on the rise. Ignoring agrarian and rural spaces, opening rivers to innumerable HES (hydroelectric power plants) activities, increasing the number of projects carried out in forest areas, starting new developments that will put heavy pressure on nature such as the Third Bridge, the new airport, and Kanal Istanbul, eviscerating preventive and supervisory instruments such as EIA (Environmental Impact Assessment), supplying unlimited amounts of natural resources to industry and trade, zoning lakes and coasts for the tourism sector with no supervision, encouraging mining, transferring copyrights and patents related to natural resources to certain fractions and groups are just some of the major issues that come to mind.

Almost all of the recent economic activities concentrated in roughly four sectors, i.e., energy, transportation, housing, and tourism, are carried out in such a way that they harm and suppress natural, urban, and cultural spaces. The methods applied to overcome protection measures, juridical decisions, developmental restrictions, and implementation difficulties are as follows: ‘centralization in the exercise of power’, ‘disabling the institutions responsible for protection’, ‘creating loopholes in regulations that require protection’, ‘misuse of legal procedures outside their purposes’ and ‘rendering legislature ineffective’ (Duru, 2015).

It is fair to say that the commons that have urban characteristics tend to be under two kinds of constraints. To start with, nearly all areas open to public use have been invaded by roads, overpasses, skyscrapers, and shopping centres. And secondly, with the state of emergency imposed after the 15 July 2016 coup attempt, the streets, parks, and squares have been subject to the strict conditions of a new period of repression. Zoning most of the earthquake assembly areas in Istanbul for construction is a good example of the first type.[6] It should be noted that Ankara is the most striking example of the second type, with the city centre being exposed to endless inspections, prohibitions, and restrictions.

b. In terms of society and culture

As mentioned earlier, commons are not limited to natural resources and urban areas. There are also some other types of commons that carry differing attributes in terms of society and culture such as languages, traditions, sciences, the internet, and arts. While it is relatively easy to make evaluations in terms of natural or urban commons, it is necessary to make a more detailed analysis of the commons related to social and cultural values.

In Turkey, when we think of the concept of ‘commons’, the first issues that come to mind are the problematics of natural resources and urban areas. There are mainly two reasons for this. First of all, due to fact that the country is still in the process of modernization, ties with the countryside still survive in some ways, and religious networks and kinship relations are strong, and even if there is no formal organization, a significant number of people can still realize their economic and social needs without entering market relations. In addition, a wide range of services and facilities such as transportation of supplies from villages, fundraising, matchmaking and marriages, hospitality, childcare, and sharing one another’s sorrow can be accessed freely, whereas in developed capitalist countries, these services can only be accessed by paying a price. At first glance, such commons are not considered to be very strong or great in number. This is because they are carried out without formal organization and without a name.

In other words, the distinction between rural and urban has begun to disappear in a very short period of time, roughly half a century, as the migratory flows to large cities have accelerated and capitalism has started to take root. On the one hand, it has also led to the decay and destruction of the urban commons, but on the other, it has also led to a continuation of traditional community behaviour patterns in urban life. In a sense, various forms of cooperation, solidarity, and sharing, all of which Mübeccel Kıray has coined ‘buffer mechanisms’, have been factors that have made it possible for social and cultural commons to stay relatively strong.

The second reason why social and cultural commons are not considered a major problem is the lack of efficient royalties and intellectual property rights and the fact that despite the tough restrictions and prohibitions imposed on them, they still have open and free access to a significant portion of the internet. It is possible to access works of art, literature, and music, for which you would need to pay in other countries, by means of copying, imitation, and reproduction.

During AKP rule, not only have the natural and urban commons opened themselves to the functioning of the economy without limit but also customs, traditions, and conventions regarding production, cooperation, sharing, and utilization have begun to fade away, losing their function and becoming meaningless in the face of the power of the market. Needless to say the pressures on facilities such as the internet, Wikipedia, and social media and their cultural values such as music, art, and science, which constitute the more intangible aspects of the commons, have been negatively influenced by the gloomy atmosphere created after the failed coup attempt.

III. Commons-based social movements

On the one hand, the resources, processes, and facilities that we call the commons refer to the very conditions that have created capitalism, such as ‘enclosure’, and on the other hand, it also reminds us of the wealth and values that people and other living creatures commonly benefit from, as well as showing the direction of new life styles built on solidarity and sharing in the future (Haiven, 2018: 35). These easy-to-access, free-to-use areas constitute the starting point of the nature of opposition movements. The movements that feed on the problems created by class, ethnicity, and gender inequalities become more and more evident in urban commons since they provide the necessary space while hosting them.

Opposition activities, demonstrations, protests, and resistances, which constitute the driving force of urban and environmental concerns, have generally been seen as new social movements. Some of the reasons for this are as follows: being guided by motives arising from cultural spaces rather than political ones; resorting to specific methods such as civil disobedience, ecoterrorism and direct action rather than traditional means of struggle such as strikes and armed conflict; aiming to change society in terms of the problem it deals with, not all aspects; generally being supported by urban and educated middle-class members; and lastly, aiming to enable participants to choose a platform and community-like temporary organizations rather than traditional bureaucratic and hierarchical mechanisms such as political parties and unions. [7]

However, although it might seem that they should be considered as a new social movement due to the abovementioned attributes, this is not the case. Owing to the fact that the commons are the source of urban social movements in a period when they are the driving force of natural and urban resources as well as the economy, they are not actually far from being class-based social movements. As David Harvey analyses in his proposition of ‘accumulation by dispossession’,[8] it is fair to say that as new social movements, urban and environmental responses, in essence, originate from the same causes as traditional, economic, and political movements.[9] Analysing urbanization movements in capitalist societies within the framework of capital accumulation processes,[10] Harvey explains the situation as follows: “Urbanization is itself produced. Thousands of workers are engaged in its production, and their work is productive of value and of surplus value. Why not focus, therefore, on the city rather than the factory as the prime site of surplus value production?” (2013: 187). The realization of this accumulation process today is as follows: rural evacuation, eviction of farmers from their land, prevention of traditional or alternative forms of production, privatization of public goods and services, appropriation of natural resources and values, commodification of nature and culture, as well as transformation of various types of property rights (common, collective, public) into private property (Adaman, et al., 2017: 18).

Generally speaking, inter-class conflict is seen not only in business but also in everyday life. The effort to provide capital accumulation and unearned incomes seems to be the strongest driving force that triggers urban social movements (Harvey, 2013: 187). In contrast to movements arising from culture and identity, such as ethnicity, race, and gender, the main problematic in terms of urban social movements emerging over the commons is, of course, the appropriation of shared resources. However, it should be noted here that there are certain interactions between the origins of movements; and even in cases where the basic purpose is to obtain unearned income and accumulate money, those who are in a rather vulnerable position, such as women as well as linguistic, religious, and cultural minorities, will experience the greatest harm.[11]

The initiators of suppression on the commons and those who create the accompanying administrative and legal conditions and those affected by the negative consequences of such suppression are not of the same class, sex, or ethnicity. As a result, emergent urban conflicts and environmental crises will not affect society as a whole. In that, those of a higher economic and social position will be able to access the methods needed to overcome these problems more easily (Çoban, 2013: 243-282). For example, in the case of damaging the commons in Turkey through appropriation or destruction, it will be women, Alevis, and Kurds who suffer the most, having to face far more challenges in their quest to find ways to avert the imminent outcomes.

The current situation in Turkey

As mentioned above, the word ‘commons’ encompasses natural resources, such as air, water, and soil, and urban spaces, such as streets, parks, and squares, as well as social facilities, such as social security, the internet, and traditions, together with cultural values, such as science, art, and music. Nevertheless, in a country such as Turkey that is still in a transitional stage economically, culturally, and geographically, the word in question is more related to the state of natural and urban commons. To put it in another way, commons-based social movements mostly stem from urban and environmental problems at large. As mentioned earlier, among the reasons for such movements are the continuation of the urbanization process, appropriation of common land, the subsistence of a portion of the population being dependent on natural resources, emergent problems in socio-economic development, insufficient social facilities, and lastly, sluggish laws and legislations pertaining to science, the internet, and copyright and patent rights.

What is meant by the word commons is the view that every single space, entity, and relation is seen as a resource that can provide capital accumulation. In a country like Turkey, whose economy is fraught with inadequacies and whose growth is not based on production but unearned incomes, it is not actually surprising to see that these areas will be the first targets to be utilized. As seen in the construction sector, which is building more and more mines, dams, and houses, the increasingly unbearable pressure on some commons may damage the livelihoods of inhabitants. Thus, as the common natural resources such as water, pastures, forests, and olive groves are taken away from these people, on the one hand they will have to acquire the resources they need for themselves, their animals, and their products from the market, and on the other, they will take a step closer to proletarianization in these places where their livelihoods are doomed to utter destruction (Akbulut, 2017: 286, 287). Therefore, it would not be wrong to say that the current economic order and the social differentiation it has created are the culprits behind the rising opposition to natural and urban commons.

Even though the urban commons movement sprawling from Gezi Park is still at the back of our mind, it does not have a strong presence in terms of quality and quantity. As can be seen in the signature campaign of the 1980s with the slogan “Güvenpark not parking lot” in Ankara, as well as the protests held against the construction of the Artillery Barracks on Taksim Square and the demolition of Emek Cinema in 2010, it is fair to say that these movements of the urban commons should not actually be underestimated.

Generally speaking, the movements over the urban commons have been initiated with the intention of protecting city squares, defending the slum areas, preventing the destruction of green areas or standing against the demolition of historical buildings at large. From this point of view, it would not be wrong to say that capital accumulation and reconstruction are the underlying causes behind such movements. And yet, as mentioned previously, it is necessary to interpret such movements that arise from urban commons from a much broader perspective. The fact that urban commons are the actual target when it comes to the settlement of cities not limited to the centres of industry, energy, and transportation but continuing to spread onto rural and natural areas, there has been an increase in the number of movements at differing levels of diversity. With this development accompanied by certain legal and administrative regulations, the resources, relations, and problems in urban and rural areas are intertwined and, in turn, have begun to affect each other. Therefore, it is no longer possible to distinguish between urban and rural movements.

In short, it may be rather misleading to focus solely on the challenges that arise from the uses of commons within the city while assessing urban commons-based social movements. In addition, excessive interventions on natural resources in rural areas are now among the factors motivating urban social movements in order to sustain urban life. There are two essential reasons for this: due to recent legal regulations and political enterprises, as urban and rural areas have begun to converge, on the one hand the spatial differences between them have begun to lose their meaning, and on the other hand emergent problems in rural areas have begun to have a negative impact on urban life. In particular, as a result of economic and managerial policies that solely target the maximization of unearned income and strengthen capitalist powers, the boundaries of metropolitan municipalities have extended as more and more villages are enclosed and agricultural land is lost, and, together with HESes (Hydroelectric Power Plants) destroying water resources, massive development projects destroy forest areas and more roads are constructed by filling seas and coastlines with nothing but concrete. Problems related to such natural resources emerge in urban life mainly in the form of water scarcity, water pollution, air pollution, and climate change as well as food shortages.

Challenges of defending the commons

With a country of economic and democratic deprivation such as Turkey, there are significant structural challenges and barriers in terms of defending cultural, ecological, or urban commons.

According to public opinion, the commons with regard to the city and environment are often considered together with more prevalent and superficial problematics such as the decrease in the quality of life, as well as the increase of pollution and the deterioration of health. More structural causes such as class relations and ownership status often tend to be ignored. A similar situation is seen in limiting food security only by providing healthy and adequate food with a sole focus on production, cleaning, and storage. It can be said that the same situation has been observed in traditional food and agriculture understanding that is far from addressing the real dangers generated by wars, conflicts, states, and food giants.[12]

There are certain factors that limit the success of social movements stemming from the commons, be it urban or rural. For example, it is sometimes believed that developments and initiatives that could harm natural resources and urban spaces will provide livelihoods and jobs for local people in poverty-stricken areas. Similarly, educated urban activists are often willing to protect natural resources, historical values, and occupied urban areas that are at high risk and, what’s more, do not want to see any kind of development of these areas. And yet sometimes they are also the ones that can perceive these projects as an opportunity for development and progress for local people.

A further factor constraining the progress of commons-based movements in some places where forests, streams, and damaged commons are located is that the indigenous population might be quite conservative. For instance, they might remain indifferent to existing problems or they might have close ties to the AKP. Alternatively they may be concerned with the economic aspect of the crisis rather than the ecological one, or they might participate in protests in order simply to defend their livelihoods.

We can also add that the urban, educated, middle-class left-leaning activists who participate in protests and demonstrations initiated in response to some damage to the commons are not appreciated by local people at times. Furthermore, they could be kept at a distance and seen as outsiders, which, in turn, can stand in the way of solidarity and commoning.

The opportunity of the commons

Turkey is a country that does not thoroughly run on the ideal principles of democracy, with a limited participation level owing to heavy-handed barriers to the freedom of expression. In this regard, as we saw during the Gezi Park resistance, it can be thought that the commoning initiatives have a significant role in revealing alternative forms of living, management, production, and sharing experiences, rather than just yielding long-lasting results.

Every now and then, public institutions, local governments, or the private sector can be effective in preventing projects that could harm the city and nature. And yet it is necessary to say that in most cases the commons-based ventures tend to be spontaneous, instantaneous, irregular, temporary, and fragmentary. In that regard, there are a number of reasons why many of these attempts no longer exist: firstly, they are generally local in nature, such as community councils, solidarity networks, occupation movements, cooperative initiatives, and seed exchange festivals; secondly, some of them last only for a period of time; and lastly, the rest are still in their trial phase with no hope of continuity, expansion, or growth and social recognition.

Factors such as the financial burden of subsistence in the city, living in apartment blocks, chaos caused by traffic and noise, pollutants generated by industrial activities, the crisis that the agricultural sector is in – for example, shelves are full of products with additives and the proliferation of genetically modified foods – in short, moving away from everything natural in our everyday lives have brought inhabitants closer to rural values and have increased interest in the natural commons. On top of that, they have accelerated the formation of new life styles that are more in touch with nature, so to speak.

Social movements rising from a small number of commons that can escape ruling economic relations and the pressure of the capitalist system have, in a way, aided local people, ordinary citizens, and university students in their attempts to enter the realm of politics that encompasses professionals, the wealthy, and the elite. It is possible to see some examples of this in the Gezi Resistance in particular.

It would not be wrong to say that these movements that are limited due to their structural deficiencies, weaknesses, and the heavy pressure under which they operate all meaning they fail to have an effective impact on the government are doomed to failure or to remain dysfunctional. But as long as they shed light on the ways of new life styles, alternative ways of construction, different forms of solidarity, and possible sharing opportunities, these movements can actually fulfil expectations.[13]

Conclusion

When the economy is in trouble, commons are the first places where the government tends to intervene. Furthermore, bearing in mind the fact that the economy is expected to worsen in the future and daily life will be filled with much bigger problems, it can be said that urban commons-based movements are not only bound to increase in number but also gain more prominence. The fact that metropolises tend to spread toward rural areas on which they are economically and ecologically dependent, legal arrangements pertaining to this process have been realized, and also the gradual disappearance of urban and rural differences are all confirming this idea.

Thanks to the new metropolitan system, those who live in rural areas and are engaged in agriculture are now subject to city centre municipalities. This will ultimately trigger the need for such commons-based social movements in these areas in the near future. We can actually see this just by looking at the fact that metropolitan municipalities, whose natural and material resources are limited, see agricultural areas as a possible income channel and they start to make significant investments – from the food sector to energy and from cemeteries to dumps – to sustain the lives of large populations dwelling in the city. However, it may also be said that the more importantly the feeling of participation in the management of enclosed villages and small municipalities has not yet been lost to the new metropolitan system.

In Turkey, spaces that are of pivotal importance for the commons to emerge and maintain their presence out of the social movements have been under threat for a very long time. Some parts of city squares, parks, and green areas have been appropriated for construction, some have been buried underneath roads and bridges, others have been zoned for commercial activities, and the rest have been barred with heavy security measures and restrictions. Therefore, both the shared commons that needs to be fought for and the places to host and sustain any such movement are either lost or damaged.

With the state of emergency launched after the coup attempt, the movements related to the commons have largely entered a period of stagnation. These years will be referred to as times filled with strict measures such as prohibitions, restraints, denial, and detention. What is worse is that natural commons are being appropriated for the service of the economy without any supervision whatsoever, while heavy security measures and restrictions are employed to prevent possible movements in response to this destruction.

It can further be said that the coffee houses project of Tayyip Erdoğan – who occasionally brings a wry smile to our faces – was started upon the realization of the gap arising from these natural and intangible commons. We can see the not-so-bizarre connection between the disappearances of streets, squares, and meeting points one by one and his promise of opening coffee houses offering free cake and tea.

There are obviously a number of challenging obstacles when it comes to protecting and improving the commons in a society where the majority of people feel excluded from the existing system, recognize the current order is not egalitarian, suffer from deeply entrenched forms of relationships, are challenged by obstacles in order to protect and develop the commons, and realize that there is no fair distribution of common resources. Furthermore, it may be expected that significant deflection and hardships could arise from adopting the values and opportunities based on common resources in a society where people believe that it is, at times, necessary to violate the laws, to stretch the rules, to behave opportunistically, to create personal exceptions, and to make the acquaintance of people in a position of power in order to make a living or to survive on a daily basis in social relations and in the urban order.

This trend, however, jeopardizes the very future of the commons in the political world, the economic structure, the education system, and everyday life, as well as in the urban order. And what’s worse, it bears the power of creating the opposite result. Last but not least, it should be noted that those who are excluded from the established order and those who feel discomfort from the dominant values and who see social injustice are much closer to searching for new ways of living, solidarity and sharing and to revealing other ways of utilizing the commons as a critical reaction to the current general tendency in society.

Notes

[1] It is possible to say that Ernst Reuter was perhaps the first person to articulate the term ‘commons’ in Turkey. In his article published in 1941, the word “commons” was translated into Turkish as ‘serbest sahalar’ -meaning free spaces: “The concept of «free spaces» called the commons, generally owned by the much-appreciated municipalities, is actually an old one.” (See Reuter, 1941: 381-411.)

[2] For the areas that the concept refers to see http://yourthings.org/tr/news/m%C3%BC%C5%9Fterekler

[3] During the emergence of capitalism, the first enclosure movement took place in the form of appropriating common land for private ownership and the destruction of common goods. Similarly, legislation such as privatization and patenting of the basic essentials for life such as water and food together with the expansion of intellectual property rights are considered modern enclosure movements. See Haiven, 2018: 27, 79.

[4] http://yourthings.org/tr/news/m%C3%BC%C5%9Fterekler

[5] res nullius

[6] See “İstanbul’daki Deprem Toplanma Alanları Halktan Gizleniyor”, (The Earthquake Assembly Areas in Istanbul are Hidden from the Public), Cumhuriyet, 17 August 2017.

[7] For class-based movements and new social movements, see: Coşkun, 2007: 99-114.

[8] The first movement, coined by Karl Marx as ‘primitive accumulation’, refers to capital accumulation through the enclosure of public spaces for communal use such as arable lands, forests and pastures as well as turning them into private property. These days when capitalism is experiencing a crisis, David Harvey has referred to Marx’s concept of ‘primitive accumulation’, and used the term ‘accumulation by dispossession’ in order to describe the process of adopting methods, such as privatization of common areas, restriction of access routes and promotion of commodification. See Adaman et al., 2017: 17.

[9] For a discussion on the fact that the two struggles, i.e., the struggle against the exploitation of labour and the struggle against the plundering and exploitation of nature, cannot be separated, see Çoban, 2013: 244, 250.

[10] For the views of Harvey and Marxism on urban spaces, see Şengül, 2001.

[11] For example, for the impact of local politics and municipal services on women, see Alkan, 2004.

[12] İrfan Aktan’s interview with Bülent Şık, “War is the biggest threat to food security”, Gazete Duvar, 20 January 2018.

[13] For a more complete explanation, see Haiven, 2018: 94.

References

Adaman, F., Akbulut, B. & Kocagöz, U. (2017). Herkesin Herkes İçin: Müşterekler Üzerine Eleştirel Bir Antoloji, İstanbul: Metis.

Akbulut, B., (2017). “Bugün, Burada: Savunudan İnşaaya Müşterekler”. Adaman, F., Akbulut, B. & Kocagöz, U. (Ed.). Herkesin Herkes İçin: Müşterekler Üzerine Eleştirel Bir Antoloji. İstanbul: Metis.

Akbulut, B., Paker H. & Adaman F. (2015). “İklim Adaleti, Müşterekler ve Yerel-Küresel Eksende Türkiye’de Çevre Hareketleri”. Access: http://iklimadaleti.org/2015/11/20/iklim-adaleti-musterekler-ve-yerel-kuresel-eksende-turkiyede-cevre-hareketleri/

Alkan, A. (2004). “Yerel Siyaset Kadınlar İçin Neden Önemli?”. Birikim Dergisi, 179.

Angelis M. & Harvie, D. (2017). “Müşterekler”. Adaman, F., Akbulut, B. & Kocagöz, U. (Ed.) Herkesin Herkes İçin: Müşterekler Üzerine Eleştirel Bir Antoloji. İstanbul: Metis.

Bollier, D. (2014). “Yeni Bir Ekonomik Sistemde Müştereklerin Rolü”. Access:

https://tr.boell.org/tr/2014/11/05/yeni-bir-ekonomik-sistemde-mustereklerin-rolu

Brent, Z. & Sharma, R. (2015). “Bu Topraklar Hepimizin”. Access: https://tr.boell.org/tr/2015/06/24/musterekler-bu-topraklar-hepimizin.

Caffentzis, G. & Federici, S. (2015). “Kapitalizme Karşı ve Kapitalizmin Ötesinde Müşterekler”. Trans. Serap Güneş. Access: https://dunyadanceviri.wordpress.com

Coşkun, M. K. (2007). Demokrasi Teorileri ve Toplumsal Hareketler. Ankara: Dipnot.

Cumhuriyet. (2017, 17 August). İstanbul’daki Deprem Toplanma Alanları Halktan Gizleniyor.

Çoban, A. (2013). “Sınıfsal Açıdan Ekolojik Mücadele, Demokrasinin Açmazları ve Komünizm”. Yaşayan Marksizm, 1 (1): 243-282.

Duru, B. (2013). “Demokratik, Ekolojik Yerel Yönetimlere Ulaşmada Köyler ve Köy Kanunu’nun Taşıdığı Olanaklar”. Birikim Dergisi, 296: 55-63.

Duru, B. (2015, 30 May). “AKP Döneminde Doğal ve Kültürel Varlıklar”. Bianet.

Eroğlu, D. (2018, 17 May). “Yatağan Cehennemine Hoşgeldiniz: 48 Köy Haritadan Silinecek”. Diken.

Fırat, B. Ö. (2011). “‘Ve Madem ki Sokaklar Kimsenin Değil’: Talan, Dolandırıcılık ve Hırsızlığa karşı Kentsel Müşterekler Yaratmak”. Eğitim, Bilim, Toplum, 36: 96-116.

Fırat, B. Ö. (2012). “Kentsel Müşterekleri Yaratmak”. Kolektif Dergisi, 12/14.

Gazete Duvar. (2018, 20 January). Gıda Güvenliğine Yönelik En Büyük Tehdit Savaştır.

Güner, O. (2014). “Siyaset ve Sınıf Gölgesinde Haziran Ruhu”. Bilim ve Gelecek, 128.

Haiven, M. (2018). Radikal Hayalgücü ve İktidarın Krizleri: Kapitalizm, Yaratıcılık, Müşterekler. Trans. Kübra Kelebekoğlu. İstanbul: Sel Yayıncılık.

Harvey, D. (2013). Asi Şehirler: Şehir Hakkından Kentsel Devrime Doğru. Trans. Ayşe Deniz Temiz. İstanbul: Metis.

McGuirk, J. (2015, 29 June). “Kentsel Müşterekler Dönüştürücü Potansiyele Sahip ve Bu Yalnızca Kent Bahçelerinden İbaret Değil”. Yeşil Gazete. Trans. Serdar Güneri.

Reuter, E. (1941). “Belediye İktisadiyatının Ehemmiyeti ve Problemleri”. Trans. Muazzez Tlabar. İ.Ü. İktisat Fakültesi Dergisi, 2 (3-4): 381-411.

Şengül, T. (2001). “Sınıf Mücadelesi ve Kent Mekânı”. Praksis, 2: 9-31.

Walljasper, J. (2015). Müştereklerimiz: Paylaştığımız Her Şey. Trans. Tuncay Birkan, Barış Cezar, Özge Çelik, Bülent Doğan, Özge Duygu Gürkan, Savaş Kılıç, Müge Gürsoy Sökmen. İstanbul: Metis.

Photo Credits (in sequential order)

Connection ![]() by Roy Sinai, Bangalore, 2007

by Roy Sinai, Bangalore, 2007

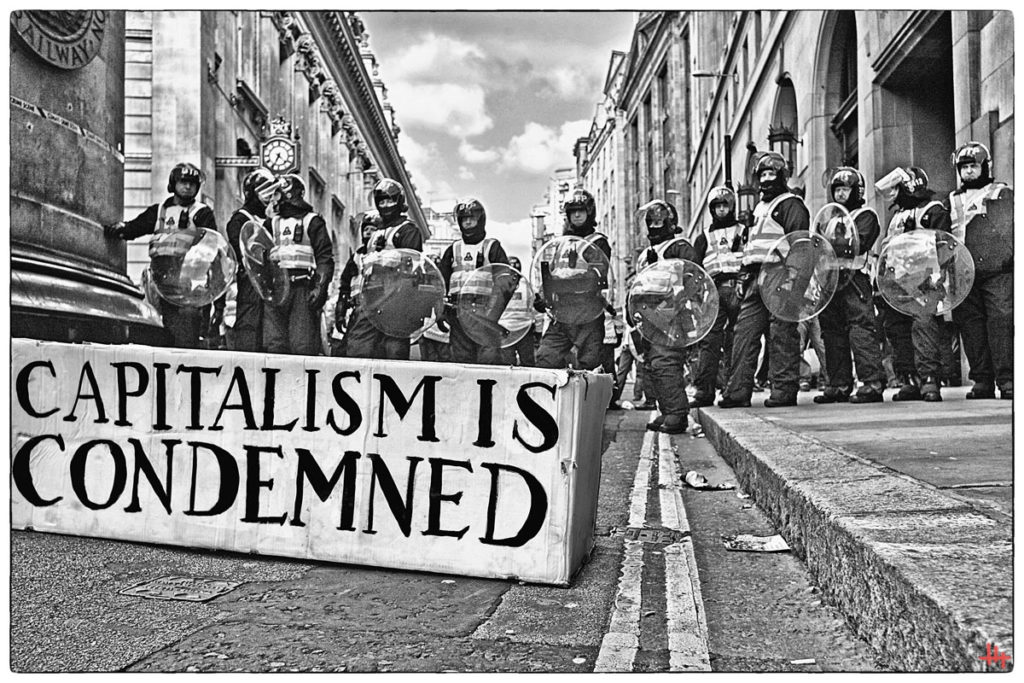

Liberate the Commons, Occupy Oakland Move In Day (1 of 31) ![]() by Glenn Halog

by Glenn Halog

“Orhan Veli” ![]() by Kasım Kurbanoğlu

by Kasım Kurbanoğlu

The urban evolution of vegetation ![]() by Dave C

by Dave C

Khimki Forest ![]() by Daniel Beilinson

by Daniel Beilinson

No Fear, Occupy Oakland Move In Day (7 of 31) ![]() by Glenn Halog

by Glenn Halog

Anti – G20 Summit – London – 2009 ![]() by The Naked Ape

by The Naked Ape

Il Grande Disco ![]() by Scott LePage

by Scott LePage

Mayday Hamburg Recht auf Stadt-Never mind the papers ![]() by Rasande Tyskar

by Rasande Tyskar

Bülent Duru was born in Ankara in 1971. Following his graduation from Ankara Atatürk High School in 1988, he won a place at Ankara University, Faculty of Political Science, Department of Public Administration in the same year. He received his Bachelor’s Degree in 1992. He completed his Master’s Thesis “Voluntary Environmentalist Agencies in Turkey in the Developmental Process of Environmental Awareness” in 1995 and Ph.D. dissertation “Integrated Approaches in Coastal Zone Management and National Coastal Policy” in 2001. He was employed by Ankara University, Faculty of Political Science in 1993 as a research assistant, and lectured on local management, urbanization policy, rural development, and environmental management. He was dismissed from the Faculty of Political Science in 2017 due to his signing the petition “We will not be a party to this crime” organized by Academics for Peace. He has produced papers, books, compilations, translated works, and studies on urbanization, local management, environmental politics, and political science.