In June 2017 mayors, councillors and activists from four continents joined the first international summit of new municipal politics. It is no coincidence that the event, ‘Fearless Cities’, took place in Barcelona or that it was organized by Barcelona en Comú, a platform set up by movement activists that runs the city government (Town Hall). Indeed the ‘Comuns’ (Commons[1]) have become a reference point for those seeking an alternative to neoliberalism and right-wing populism. This is because of their origins – mayor Ada Colau was the public face of the inspiring PAH housing movement – and the breakneck speed by which they took office – months after setting up their platform! Also they have shown that politics can be done in more participatory and innovative ways.

A number of practical changes have been made in office. In response to firms cutting energy supply to those not able to pay their abusive prices, the Town Hall[2] has created a public (and sustainable) energy-management corporation. Because spiralling tourism has made rents unaffordable to many residents, the Town Hall has begun to regulate this powerful sector. Colau led other mayors to pressure a conservative Spanish government into accepting many more refugees. Public procurement now favours firms that belong to the ‘social economy’ (including cooperatives), offer better working conditions, or employ greater numbers of women and disabled people (Blanco, Salazar, & Bianchi, 2017). Municipal facilities are being handed over to communities for self-managed social and cultural projects (Junqué & Shea-Baird, 2018: 145). Women’s services have been municipalized, and all policies are tested for their specific impact on women (Pérez, 2018: 36). Importantly for the future, mechanisms have been introduced for residents and other associations to be able to present proposals for laws at the Town Hall (after collecting a certain number of signatures). Through such measures the Commons have shown there are practical alternatives to a political system that offers only neoliberalism with different degrees of authoritarianism.

This article looks at how such positive changes came about. But it also examines the limits of three years of Commons government. The general opinion in Barcelona – as has been voiced by spokespeople for a wide range of social movements – has been that transformations have been uneven and slow.[3] As a result, enthusiasm for (and involvement in) the project has declined. Any serious assessment of the Commons experiment must also try and identify why this is so, which is what is attempted here.

The piece begins by identifying how grassroots social movements made the project possible. Then it looks at the theories influencing its development. Next, I provide a brief history and description of how the Commons are organized and analyse their record in office, focusing on the key areas of housing and tourism. Lastly I look at how their relationship with movements and the institutions has led to mixed results and ask whether other political strategies are needed.

The movements that made Barcelona en Comú

Two movements have been crucial to the development and electoral success of the Commons: the PAH, which was created in Barcelona in 2009; and the radical-democratic 15-M movement (“the Indignados”), which occupied squares and held protests and mass meetings across Spain in 2011. Their importance to BeC was stated in an article by Kate Shea-Baird, a leading member of the platform and prolific writer in English on the topic. She wrote that “Barcelona en Comú” (Barcelona in Common) “is the electoral result of the PAH” and that “you can do a map of the Indignados camps and the cities that the municipalist platforms won and they are basically one to one” (2018). Both movements were crucial in developing what neo-Gramscians call “counter hegemony” against the ideas of the establishment. And the PAH provided very many of the activists that created BeC.

The Platform of People Affected by Mortgages (PAH according to its Spanish initials) is a grassroots movement with over a hundred branches, including around thirty in the Barcelona area. It has carried out civil disobedience to block over a thousand evictions, and has forced a reduction in abusive bank practices by which failure to meet mortgage payment leads to life-long debt (as well as losing one’s home).[4] Colau and the platform became cause célèbres when the PAH collected a million and a half signatures in favour of housing reform and Colau spoke at a Congress meeting where she described the bankers’ representative present as “a criminal” Videos and tweets of her refusal to retract the comments went viral (Durall & Faus, 2016). The conservatives ruling at the time blocked even discussing reform, ignoring a million emails sent to MPs in its support! The issue dramatically highlighted the gap between the people and government (as well as the Socialist opposition, who argued that life-long debts were necessary for the health of the economy). Polls showed nine out of ten people supported the PAH, a proportion that hardly dipped when the PAH more controversially verbally harassed MPs and bankers responsible for the housing crisis in the street (Colau & Alemany, 2013). Colau’s name was quickly put forward when from 2013 activists began to discuss standing candidates in elections because of the public respect she had earned confronting a self-serving and corrupt “political class”.

But for people to turn so strongly against that class (and for the PAH to grow into a mass network) the 15-M movement was needed. This was a truly historic development as it was a radical movement that (according to surveys) one in five people had some contact with. Through discussion of a wide range of social and other grievances (many linked to the crisis, others longer term, such as corruption) the idea became crystallized that “they” (politicians and other representatives[5]) “do not represent us”, which became 15-M’s main slogan. For many participants the idea meant that we should exercise direct rather than representative democracy. As a result of this sentiment all political parties, including radical-left parties, were banned from the squares. As a (Catalan) Commons leader wrote at the time, however, others saw “they don’t represent us” as saying the existing representatives did not represent us (Domènech, 2014).

It is likely that these “two souls” in the movement – the more and less radical participants (Taibo-Arias, 2012) – were later attracted to municipal politics, which promised both an electoral alternative to the established parties and participatory democracy. But before such projects were off the ground, 15-M prepared their ground by creating a crisis for their main competitor, the governing Socialists, whose support plummeted after the occupations. This would lead the main two parties’ share of the vote to fall from eighty to fifty percent of the total.[6]

As a range of social scientists have identified, movements under crisis and austerity, such as 15-M, differed from earlier movements (for example over “global justice”) in that they adopted a “majoritarian” political approach. This meant they consciously tried to involve most citizens through inclusive discourse (references to being “the 99%”), consensus decision-making (Della Porta, Masullo, & Portos, 2015: 3) and communicating through commercial social-media (e.g Facebook and Twitter; Gerbaudo, 2012). 15-M and Occupy consciously framed themselves as confronting those from “below” with those “above”, rather than being “left” versus “right” (Errejón, 2011). Not dissimilarly the PAH described itself as being a movement of “citizens” (even though the people losing their homes tended to be from a narrower social group, the working-class poor[7]).

If 15-M, which most of the population sympathized with,[8] brought about a tectonic cultural shift, the PAH channelled the new outrage (indignación) in an effective direction. But even the PAH’s victories – and those of other “horizontal” movements that developed at that time – were small compared to the scale of the rollback of social rights that was taking place at the time. Public services were being weakened and the total number of evictions would reach half a million. There was a “sense among activists” that they had hit a “glass ceiling” and “that it would become increasingly difficult to sustain the level of mobilization” taking place (Castro, 2018: 186). This feeling was perhaps inevitable due to the absence of a powerful strike movement that could stop the government and the powerful forces, including the EU, standing behind it.

In 2013 many activists who until then had zealously defended their movements, remaining autonomous from parties and the institutions, appeared to do a 180-degree turn, now discussing standing in elections and “taking the institutions”,[9] and in some (impressive) cases studying and writing on municipalism in history (Observatorio Metropolitano, 2014). One of the first new initiatives created was the platform Guanyem Barcelona (Let’s Win Barcelona, later renamed Barcelona en Comú), which involved large numbers of people in meetings and on-line voting. This way of organising and the organization’s very name reflected the majoritarian and democratic nature of the Squares.

Common theories

While the movements shaping the “new politics”, the ideas of individuals and already existing organizations have played an important role as well. There is no single theory behind BeC, which is a fairly heterodox project, but there are some political ideas that have left an imprint. One of these, as I shall show, is feminism, which has been a notable feature of the radical social movements since the 1990s in the form of both specific feminist spaces and as an approach adopted by broader spaces (such as the squatters or radical pro-independence movements; García-Grenzner, 2018). And it is a movement that has risen while others have subsided: firstly it confronted abortion restrictions (in 2013-14), and secondly held an historic women’s strike (this year).[10]

Yet the two ideas that most shaped the creation and development of the ‘Comuns’ are those of “proximity” and “the commons”. For BeC, “[t]he proximity of municipal governments to the people makes them the best opportunity we have to take the change from the streets to the institutions” (Barcelona en Comú, 2016). Radical municipalists have insisted that this requires creating local “sites of direct decision-making” by people (Observatorio Metropolitano, 2014: 143) and reversing “the logic of representative democracy” (Castro, 2018: 187), a view that echoes the writings of the US libertarian Murray Bookchin (Bookchin, D., 2018) as well the radical view in the Squares. Sometimes this idea is tied in with seeing the city as the privileged arena of struggle and transformation, as defended by the Marxist urban theorist Henri Lefebvre, because it is inevitably the site of dispossession, gentrification, cultural battles and an agglomeration of people. A central role for the city was attributed by a mayoral aide from Galicia (north-eastern Spain) participating in Fearless Cities who wrote that an “archipelago” of “rebel cities” was “democracy’s best hope”. For him this is because “traditional political institutions have lost power along with nation-states” (Martínez, 2018: 23-25).

The name “Barcelona in Common” reflects another important strategic idea in the new municipalism: the fight for the commons. The concept had become important over the previous decade in the milieu from which the organization developed. Yet there are different interpretations of what the term should mean. This was clear in an interesting debate between one of the key intellectuals in BeC, Joan Subirats, and the young sociologist Cesar Rendueles. For both, the Commons approach rejected both neoliberalism and statist “socialism” in favour of seeking collective ownership and running of “public goods”.

It takes its name from the cooperative farming of common land in the pre-industrial period, which gave people the right to use such land but also the obligation to use it carefully. For Rendueles creating the commons made sense if these reclaimed spaces were used to help material (class) conflicts in society (which they could do by creating strong cooperative networks and introducing a basic income; Subirats & Rendueles, 2016: 11-12). Subirats, however, puts the emphasis on “the commons” being a “promising and exciting term” that could overcome the lack of appeal of politics at the nation-state level (which, like Martínez, he puts down to the impotence of the nation-state today; Subirats & Rendueles, 2016: 13). Put together with the nostalgia he demonstrates toward post-war European social-democracy (for being less unequal and thus “avoiding conflicts”; Subirats & Rendueles, 2016: 42), this approach could be seen as an example of what Shea Baird describes as municipalism “by necessity” (2018), which here seems to be little more than regenerating traditional social democracy from a local base. Rendueles, therefore, is probably right to suggest that the “vagueness” of the “commons” concept, as well as its popularity, is leading it to be interpreted in different ways (Subirats & Rendueles, 2016: 11). In the Comuns project both radical and social-democratic approaches to the commons would play a role.

Taking a town hall

The process of creating the municipal platform in Barcelona was impressive on many levels, as it was in many other Spanish municipalities. Between June 2014 and May 2015 many thousands of city residents participated in some kind of democratic exercise. At the platform’s presentation in Central Barcelona there was an exciting militant atmosphere (with talk of going from “occupying the Squares”, to “occupying the Town Halls”). It was striking how most speakers, including those from the floor, were activists in the PAH or residents’ movements. Among the 2000 people present there were many from the 15-M generation as well as older people. Colau announced that Guanyem Barcelona would stand in the 2015 elections if they successfully collected 30,000 signatures in three months (which was reached). Other organizations and individuals were encouraged to join the project.

In its public events Guanyem aimed to involve people “to prove that there are other ways of doing politics” (Barcelona en Comú, 2016). Well-attended meetings in neighborhoods were held to present Guanyem’s basic ideas but also to find out about local realities, discuss doubts, collect contributions and (in the organization’s words) “ask ourselves what is needed to win in Clot, Sants, Nou Barris, etc.?”, referring to the local issues in different neighborhoods.[11] Later “citizens demands” would be identified for each local area.

In the autumn a code of ethics was discussed, including in open meetings, and adopted. It included the requirement of limited and revocable mandates for representatives and for them “to make public their agendas and all their income sources, wealth and capital gains”. The organization also had to make its revenue and spending public (Castro, 2018: 195; Barcelona en Comú, 2016). Also the organization choose to fund itself without taking loans from banks (Barcelona en Comú, 2016). This was because banks have used loan repayment as a lever to influence the policies of the traditional parties (Colau & Alemany, 2013: 9). Hundreds of volunteers ran a campaign that raised 90,000 euros through crowdfunding, which was more than doubled though small donations (Junqué and Shea-Baird, 2018: 65). The ‘Comuns’ are understandably proud of these measures and their implementation.

The process to create the election programme was also inspiring. It was developed over many months in 2014 and 2015 through sectorial commissions holding meetings to discuss proposals and gather expert knowledge. On-line consultation was also used. In February the programme was presented. According to the platform, 5,000 people had been involved in twenty neighborhood groups. They put forward 2,500 measures[12] and prioritized forty. The programme presented later (in April 2015) stood out as detailed and well-informed and conveyed the “collective intelligence” through which it was built (Barcelona en Comú, 2015b).

A more controversial aspect of the project was its progressive “convergence” with other political forces. Negotiations with these were held early on and then evaluated (with the content of negotiations made public, Barcelona en Comú, 2016). The eventual result was the inclusion in the platform of the Barcelona branches of the Euro-Communist ICV-Verds, Podemos, and smaller parties and citizens’ movements. The incorporation of ICV-Verds was particularly significant. They had been junior partners in city and Catalan administrations and were in part responsible for a city model that since the preparations for the 1992 Olympics, had been obsessed with attracting tourists and capital. Also an ICV leader became hated after his ministry in the Catalan government badly repressed students and other groups. By including ICV, Guanyem precluded reaching agreements with the other interesting municipalist project: the anti-capitalist and pro-independence CUP. This at the time had 101 councillors and around 20,000 activist members in Catalonia. ICV, which already had municipal seats, would provide BeC with additional funds (a partial exception to Guanyem’s funding ethics), as well as institutional experience, which later would help increase ICV’s influence in the different Commons projects.

The alliance between the different organizations was not simply a coalition. Indeed the term “convergence” (“confluencia”) was preferred in the processes of regroupment that took place at the time across the Spanish state.[13] This preference was, first, because the final forms of alliance “went beyond established political identities” (Rubio-Pueyo, 2017). But secondly, and more importantly, when choosing election candidates and coordinators, most of the new platforms used open or semi-open systems of voting. Barcelona en Comú used a relatively closed system, where a slate of candidates was put to a vote,[14] and this (it seems) was the result of negotiations between the different parties and organizations in the new platform.[15] Some descriptions of the new municipalism suggest that its desire to include parties to the left of the Socialists was a sign of “15-M inclusivity”. But 15-M rejected including all parties, including the Communists, and the new convergence is probably best seen as expressing the view of the more moderate wing of the movement (or simply as a shift rightwards).[16] And the Commons went further in this direction when, a year into government, they temporarily formed a new coalition with the Socialists and incorporated four of its councillors into the municipal government.[17]

Five months before the elections, and despite the name Guanyem Barcelona having become known by many, the platform was blocked from standing when a fake party officially registered the name. This ensured that the face and name of Ada Colau would dominate the campaign (rather than the new name Barcelona en Comú). In February BeC presented its “emergency plan”, which called for creating decent jobs, guaranteeing basic social rights, reviewing privatizations and projects contrary to the common good and a financial audit of the institutions (Barcelona en Comú, 2015a). The campaign around this had a real buzz apart from when Ada Colau spoke before stony-faced businesspeople, as shown in the documentary Ada for Mayor (Durall & Faus, 2016). The day of the elections, 24 May 2015, was a historic day for Barcelona, Catalonia and Spain. Several new platforms ended up governing big cities. BeC won the highest amount of votes and 11 seats (with the CUP winning a further three). This was out of 41 seats, making it a very minority government and constrained in its possible actions, but the result was still stunning!

How Barcelona en Comú is organized

The Comuns insist that the how in politics is as important as the what, and that the way their organization should operate should reflect the kind of society it wishes to bring about. Therefore I shall begin my examination of the platform’s record by providing a short description and assessment of how BeC is organized and decisions are made. The first notable way by which their political objectives influence their way of doing politics is through “feminization” of the organization. Most visibly BeC has produced the first female mayor of Barcelona and a municipal team of whom 60 per cent are women, and 50 per cent of all BeC coordinators must be female (Pérez, 2018: 34; Castro, 2018: 192). Mechanisms against gender inequality are applied in the organization’s processes: meetings are held at the times most compatible with childcare, and contributions in them are kept short (to avoid men talking more and dominating decision making) and must alternate between women and men to guarantee that women participate at least 50 per cent of the time (Pérez, 2018: 34-35).

Despite the abundance of writing on the BeC method and structures, it is not always easy to identify exactly how they work in practice (and whether they live up to the claims made about them). The organization’s current structure was formalized in a plenary soon after winning office and separates its institutional and political platform spaces. This gave greater autonomy to the organisation from the municipal group but also gave more independence to elected representatives! The institutional section is organized around the municipal group and district heads and these have gained greater weight in the whole project over time, which has led to some tensions and criticisms.

On the “non-government” side the “coordinating team” (“coordinadora”) is normally presented as being the key body. It includes forty representatives of which four are from the municipal group but many more from neighborhood assemblies (allowing it to act a “bridge” between the city and districts). It also contains an eight-member executive team responsible for implementing coordinadora decisions. Some observers believe that this team is the effective leadership within the platform (and it also has close links with the municipal team). BeC itself says it has the “responsibility of laying down the organisation’s political strategy”[18] (but that so too does an elected “political council” of 150 members).[19]

There is broad involvement in BeC, for example plenaries are held every two or three months, in which the 1,500 people “active” in the organisation can participate,[20] online political consultations also take place. However, again, it is clear that things are not as horizontal as they seem (something suggested by the Comuns when they claim to combine “effectiveness” with “horizontality” in their organisational model; Barcelona en Comú, 2016). Even by BeC’s own accounts key political discussion takes place only where people have been elected to bodies.[21] And from the start the systems applied to voting on electoral lists and key bodies were of the “slate” kind that encouraged least proportionality and plurality[22] (Castro, 2018: 197).[23] The result has been a system that encourages bargaining behind closed doors and therefore disempowers the base. It is worth noting that some radical municipalists maintain that BeC was among the most top-down of the new municipal projects (Rodríguez-López, 2016). On the other hand, in office BeC has taken steps to increase the relative power of the movements compared to the political system: for instance introducing mechanisms by which social movements and residents’ associations can present a ‘Popular Legislative Initiative’ to effect policy change.

Mixed results in office

A year after taking office around half of the measures in BeC’s Emergency Plan (for their first months in government) had been implemented successfully (Corominas, Moreno, Riera, & Romero, 2016). This has meant a great many positive transformations of the kind described at the beginning of this article. It also showed that many central changes promised were not materialising. There have been mixed results in relation to immigration. Anti-racists celebrated when the Town Hall closed a detention centre of the kind Colau described as “worse than prisons” and “racist”, because they “discriminate against people because of their origins” (Colau & Stobart, 2018). But because of the Town Hall’s limited powers in this policy area, this was done by means of a formality (the centre’s lack of a local operating licence); and central government predictably re-opened the centre, making the protest only symbolic. The Colau administration’s support for the pro-refugee movement is also welcome (although some pro-asylum activists have been less impressed by the institution’s commitment to their struggle once the issue stopped being major news[24]).

But during a Town Hall event in solidarity with refugees Colau and her Deputy were heckled by African migrants and supporters. The migrants were undocumented street vendors that, despite the change in local government, have continued to be harassed and abused by the municipal police, the Urban Guard, as well as other forces. Faced with this situation the mainly Senegalese migrants formed an impressive Union of Street Vendors, whose demands include having safe spaces and the Town Hall putting pressure on the central state to regularize migrants. Police pressure on migrants does seem to have relaxed but this may be linked to the riot that took place in Madrid in March after a member of the same union died during a police chase (under a Commons-type administration!). Jesús Rodríguez, a respected alternative journalist, told me he thought the Town Hall has not wanted to take on the Urban Guard (Rodríguez & Stobart, 2018), whose management and union made several protests about serving under Colau at the beginning of her mandate. These included their chief resigning, and complaining about her law-breaking in the PAH.[25] Rodríguez added that BeC also felt pressure because migrant street vending is an issue over which the media, opposition forces and many local traders are united in their opposition (Rodríguez & Stobart, 2018). When the Town Hall created a work cooperative helping 15 migrants abandon street vending and increase their chance of obtaining residence papers, the union understandably rejected the initiative as tokenistic. The street-vending issue has been a notable source of tension between social movement activists in general and the municipal administration.

Housing and tourism

In recent years rents in Barcelona have rocketed (for example by 17 per cent between 2014 and 2016; Castro, 2018: 199), and in some neighborhoods tenants spend 60 per cent of their incomes on rent. This situation has developed thanks to laws reducing lengths of tenancy agreements, and the contrast between increased demand and reduced supply of rented property.[26] Moreover, supply of rented property has decreased because home rental to tourists (through Airbnb) has also rocketed to become a considerable source of income for many locals. Other locals are getting priced out of living in the city. And added resentment is caused because neighborhoods are being transformed to cater for the tastes and pockets of tourists rather than local people. This situation has led to the emergence of both a new Tenants’ Union and an Assembly of Neighborhoods for Sustainable Tourism (ABTS).

Because of BeC’s links with the PAH and urban movements, there were many expectations that it would tackle the “double and interrelated” rent and tourism bubbles (Castro, 2018: 198). And important steps have been made in this direction. In 2016 the Colau government forced Airbnb to stop advertising unlicensed apartments that totalled 40 per cent of apartments included on the platform. This was by fining the company 600,000 euros.[27] It has suspended giving licenses to new pubs, restaurants and discos in tourist areas (Blanco, Salazar, & Bianchi, 2017). In 2017 the Town Hall passed a Special Tourist Accommodation Plan (PEUAT), which introduced a non-growth and redistribution policy for accommodation used for tourism (Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2017).

These measures, however limited, have been introduced despite hundreds of legal appeals against them; appeals that have been supported by city lobbies, the media and the large opposition parties. They also encountered internal resistance from the Socialists when this party shared government with BeC.[28] It should be noted that leading BeC members recognize such initiatives were made easier by the active protests of the ABTS and related movements in the neighborhoods (which, for example, helped overcome opposition to change from other parties in the Town Hall; Junqué and Shea-Baird, 2018: 133-134).

Positive steps also have been taken in the area of housing. A mediation unit now intervenes in almost all cases where evictions are announced. The Town Hall has introduced rules to ensure tenants keep their homes after municipal interventions, and investment in housing has quadrupled (albeit from a very low level; Barcelona en Comú, 2018). In June the Town Hall agreed to compel firms constructing new buildings or doing substantial renovation to devote 30 per cent of the property to social housing.[29]

The incorporation of large numbers of housing and urban activists in the Commons project decapitated and depleted the relevant movements. But in Barcelona both movements have regenerated. This is partly because, as one municipalist writes:

“the paradox is that after two years of…a government that emerged from social movements, the housing crisis is possibly worse than ever” (Castro, 2018: 200).

And despite all the mediation, evictions continue on a mass scale, at an average of 10 per day last year (Bellver, 2017).

Moreover, the movements have sometimes expressed their disappointment regarding the Town Hall’s progress in making real change. The PAH celebrated the Colau government’s announcement that banks would be fined if they kept houses empty and, more specifically, that the “bad bank” (Sareb[30]) should hand over 400 empty units. But PAH then publicly complained about the slow and inadequate enforcement of these policies.[31] For example in 2017 a movement spokesperson denounced the fact that only four fines had been given to banks despite 2000 flats remaining empty (Bellver, 2017).

Movement leaders argue the need for much more radical changes than have been contemplated, including large-scale public investment to expand the public housing stock. (This currently is at an extremely low one per cent of total housing; Castro, 2018: 200.) But the new municipal politics in Catalonia and Spain, including some of its more left-wing versions, tends to rule out big increases in spending that would contravene the municipal deficit limits imposed by central government during the crisis.[32] The only big Town Hall of Change that has openly challenged the law was Madrid, whose finance councillor presented a much-increased budget. Yet after months of pressure from the finance minister, the councillor was sacked and budget controls accepted, which created major division in the municipal team.

Why the limitations?

In response to criticisms over progress, Commons representatives talk of the need for the project to “manage people’s expectations” (see Gala Pin in Bellver, 2017). But the fact is that while Colau and her comrades warned that change would not be straightforward, they themselves encouraged these expectations. Even a few years into office aspects of the Emergency Plan, including transforming work and the economy, have not been fulfilled. Previous administrations have failed to fulfill promises, but BeC stated explicitly it would never do this.

The limitations to progress are explained by the Commons as owing to factors beyond their control. And, yes, governing as a minority and requiring the votes of socio-liberal forces (whether Socialists or the pro-independence ERC) to pass policies does make change difficult. The Commons have been subjected to legal and economic threats on numerous occasions, including for wanting to hold a “multi-referendum” asking residents if they wish to remunicipalize water. Such reactions could be seen as a low-intensity war. When the Commons have made positive changes, a universally hostile media has failed to report on them adequately.

But the political strategy BeC has adopted has made it harder to overcome obstacles. Critics of BeC argue that the Town Hall is too obsessed with its popularity (or polling[33]), and is therefore, for instance, more concerned by the opinion of voting traders than non-voting African migrants. This then leads to excessive pragmatism vis-à-vis other political formations. As well as incorporating parties with little interest in doing politics from below, it even ended up governing with the party most responsible for Barcelona’s urban rifts.

In her campaigning and writing (also with Adrià Alemany, another influential figure in BeC) Colau showed a strong understanding of the way finance exercises its power in politics and society (Colau & Alemany, 2013). She warned that this would mean a backlash against a Commons government. But the Commons seem to have been less clear about the ease with which municipal institutions can be wielded as emancipatory tools (in other words how easy it would be to implement the commons through them). Issues such as the re-opening of the detention centre have shown that local government has much less power than institutions at higher territorial levels. For all the municipalist talk of the weakened nation state it has been central government that has been key to holding back municipal autonomy, in particular through fiscal discipline. This has even led to the depressing situation where new Town Halls boast having “balanced the books” better than the conservative central government[34] (Fundación de los Comunes, 2018).

It is possible that some realization of the limits of the local is what led Barcelona en Comú to intervene at a Spanish and later Catalan territorial level through similar political convergence to that achieved in Barcelona. But in the process the organization demonstrated something that was increasingly noticeable locally: that a project based on democracy and proximity was giving way to a more traditional left reformism. To be fair, Colau, Shea Baird and leading BeC members often imply they are not fully convinced about having moved the Commons beyond the municipal sphere,[35] and the Fearless Cities project could very well be an attempt to overcome the limitations of the local without abandoning the original commons approach.

Questions must also be raised about about how much the Commons understood the nature of the institutions and party politics when they decided to enter both. The rationale behind the adoption of an ethical code for representatives (and the impressive effort put into it) was to “end the privilege that has led political representatives to be out of touch with ordinary citizens” (Barcelona en Comú, 2016). And Colau and Alemany wrote that parties become “hostages” to corporations by depending on corporate donations to fund their campaigns (Colau & Alemany, 2013: 9). There is degree of truth in both assertions but there is much more to the failure of institutional politics. Here is not the place for a detailed analysis of the role of the institutions under capitalism, suffice to say that both their non-elected administrators (police chiefs, civil servants…) and central function (arbitrating between individuals, including competing capitalists) actually makes them part and parcel of capitalism and the class system. This means that if a government is elected that tries to break with either, pressure can be exerted from both the outside[36] and the inside of the institution (as we have seen in the case of the Barcelona police).

Indeed the Commons reveal a utopian view of the institutions in their slogan to “take back” the institutions. This begs the question of when were the institutions ours? Subirats reminisces about a golden (social-democratic) age that hardly existed in Spain (thanks to forty years of far right dictatorship, followed by Socialist governments that quickly embraced neoliberalism). And even in northwestern Europe the post-war experiment in redistribution and welfare-state capitalism is probably best seen as an anomaly (fed by an unusually long period of economic expansion), rather than the rule.

The democratic revolution

Resistance to change can come from powerful quarters: central government, large multinationals, municipal bureaucracies, etc. But it can be countered through the municipal institutions if there are movements outside also pushing for change. We gained a glimpse of this when the assemblies for sustainable tourism helped the Commons regulate tourist accommodation. But movements sometimes take complex forms and political leaderships can help them go forwards or backwards. In this regard one of the biggest mistakes made yet by the Commons has been over the Catalan independence referendum. The problem was not that the organization has an “ambivalent” attitude to independence (Shea-Baird, 2016), as many people who joined the protests over the referendum do. Rather it is that when a mass movement for national independence morphs into a broader and more radical struggle for democracy, the success or failure of this attempt will likely shape all other attempts at political transformation. This is exactly what happened in the autumn last year with Barcelona as its hub.

After a major spontaneous revolt began on 20 September in response to police raids and arrests at Catalan government buildings, the seriousness of the conflict became apparent to the world (Stobart, 2017). The Rajoy government was completely against allowing a “legal” referendum and therefore the only way to exercise the right to decide over independence (a right that BeC formally supported) was through a unilateral referendum, as was called by the Catalan parliament. But even while neighborhood assemblies organized across Catalonia to occupy polling stations (and ensure they were not closed by police), the Barcelona government refused to recognize the referendum (or prevented municipal facilities from being used for the vote). The mass mobilization on the day of the referendum (which BeC did support) and the improvised general strike two days later (Stobart, 2018b) was arguably the closest thing yet to the “democratic revolution” that the Commons said they stood for. Yet Colau and the Commons continued to be “equidistant”, spending the coming weeks blaming the Catalan as much as the Spanish government for the repression that took place.

Colau justified not treating the referendum as binding by saying she represented the whole of Barcelona and that the city was divided over the matter. A great many Catalans saw this as motivated by BeC having strong electoral support in neighborhoods mainly opposed to independence. But the problem was also strategic. Colau knew that no other referendum was possible under Rajoy. So effectively she was saying she could not align herself with the section of the population defending self-determination, which she herself had always defended, because she had to represent the section of the population that did not.

This reminded me of the British Marxist Chris Harman’s observation in the 1960s that social-democratic parties (opportunistically) fail to defend the ideas of the most progressive section of the working class because they seek to represent the whole of the working class, including its less conscious sections (Harman, 1968-1969). By sitting on the fence during the Catalan crisis, the Commons has distanced itself from a movement that has created new forms of counter-power in the neighborhoods, particularly working-class ones (Stobart, 2018a).[37] It is difficult to imagine how this helps a genuine commons project.

The conclusion I would reach from the analysis offered throughout this article is not to stop intervening in the institutions. But the question must be asked as to how such an intervention is best done to achieve emancipatory results. Should we always aim to “win”? Or should we see the institutions as enemy territory in which representatives can only act as “Trojan horses for the movements” (i.e. mouthpieces for a more important struggle outside)? The latter strategy was that of the first CUP MPs in the Catalan parliament and I believe deserves more attention.

All the same I believe we can learn many positive lessons from BeC. Its road to the Town Hall was really impressive on lots of levels. And its victory greatly lifted those fighting for a better city and world, and demoralized our opponents. Many positive changes have been made since, despite all the limitations. The Commons have demonstrated on numerous occasions that there are better, more-democratic and more egalitarian ways of organising politically than those of the traditional left. In Barcelona Town Hall the Commons have disorganized those parties that use the institutions to disorganize our side. Only a sectarian would not celebrate those achievements.

Notes

[1] Here the Commons mean Barcelona en Comu, which won the Town Hall in the elections.

[2] The city government.

[3] This was a clear finding from a survey by an investigative journalism site sympathetic to the Comuns carried out two years after BeC came to office. In a minority of cases movement spokespeople reported mainly positive evaluations, and in a minority, predominantly negative (Bellver, 2017).

[4] This happens when the “recovered” property is auctioned at a lower price than the original purchase price. After 2008 this meant on average a victim would owe the bank a third of the original price of the house for which the mortgage was awarded. The difference would be automatically taken from wages received.

[5] The leaders of the large unions.

[6] This took place even before the new left-wing party Podemos emerged as a serious competitor.

[7] Rodríguez-López, 2016.

[8] https://elpais.com/politica/2012/05/19/actualidad/1337451774_232068.html

[9] It is also possible that for some autonomous movement activists, organising in party-free spaces was about ensuring that the movement only acted according to its own interests but that change was still expected to come through a partially responsive political class, which has become less and less the case, particularly in the austerity period.

[10] The central role of the feminist movement in current struggles is given a fascinating analysis by The Fundación de los Comunes (2018).

[11] Source: https://barcelonaencomu.cat/es/como-hemos-llegado-hasta-aqui

[12] https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/politica/Barcelona-Comu-presenta-ciudad-democratica_0_381462113.html

[13] “The Spanish state” is often used by leftists, particularly in the Basque Country and Catalonia, to describe Spain. It is preferred because it avoids treating “Spain” as simply another nation state.

[14] Only those in charge of districts were elected through primaries.

[15] In a video diary Colau complained that the negotiations to incorporate left parties and movements in BeC were “a big blow” because instead of these wishing to cooperate over common objectives, they fought over their “share of power” (Durall & Faus, 2016).

[16] The initiators of Guanyem Barcelona/BeC tend to be from activist generations earlier than 15-M. Some Guanyem Barcelona spokespeople, including Colau and Subirats, already had close relationships with ICV-Verds.

[17] This change was supposedly in order for policies to be passed more easily but, predictably, it led to policies being softened and even abandoned.

[18] https://barcelonaencomu.cat/es/organigrama

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] This is something I saw for myself when I attended a member’s plenary in January 2018. Despite only being a month into Madrid’s suspension of Catalan autonomy and the imprisonment of several Catalan leaders (for organising a mass referendum on independence) the only political issue discussed was the following year’s elections!

[22] However, Comuns leaders were included in slates of members from different participating movements and parties.

[23] The processes of choosing candidates in Galicia and Madrid have been held up as much more democratic (Rodríguez-López, 2016).

[24] This was made clear to me in conversations with anti-racist activists and is suggested by a migrant-rights campaigner in the Crític survey (Corominas, Moreno, Riera, & Romero, 2016).

[25] https://www.eldiario.es/catalunya/relacion-Guardia-Urbana-Colau-claves_0_401760803.html

[26] A factor in this is that since the post-2008 wave of evictions, banks are more cautious about giving out mortgages and citizens are more cautious about taking them out (Bellver, 2018).

[27] https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/jun/02/airbnb-faces-crackdown-on-illegal-apartment-rentals-in-barcelona

[28] https://www.elperiodico.com/es/barcelona/20171113/los-sectores-economicos-de-bcn-temen-una-fase-de-paralisis-por-la-soledad-de-colau-6421146 The agreeement with the Socialists (PSC) was broken after this party supported suspending Catalan self-government during the crisis over the referendum. However, already there were big disagreements between the PSC and BComú on different issues.

[29] https://www.elperiodico.com/es/barcelona/20180618/acuerdo-vivienda-social-barcelona-6884056

[30] The Sareb was created by the Spanish government to manage the assets of nationalized banks.

[31] https://pahbarcelona.org/es/2015/12/01/carta-de-la-pah-a-ada-colau-alcaldessa-de-barcelona/

[32] The conservative Finance Minister (Montoro) introduced the measure as part of a combined austerity and territorial re-centralisation strategy.

[33] This argument was made by the then-Deputy Mayor of Badalona in an interview (Téllez & Stobart, 2017).

[34] Europe seems to have allowed Rajoy and his ministers to do this to avoid further social and political unrest that could bring about a left-wing government in Spain (at a time when Europe was trying to subdue and isolate the Syriza government in Greece).

[35] It is notable, for example, how invisible the Catalan Comuns (Catalunya en Comú) project is in the political writing of BeC leaders.

[36] Including by the actors Gramsci included in the “integral state” (or actors whose social role is in relation to capitalist states and sub-states).

[37] It probably also has unintentionally facilitated the growth in Spanish nationalism that has taken place since last year (which benefits from being able to present the struggle for self-determination as being only by nationalists and elites), while making it harder to push that struggle in a (needed) left-wing direction.

References

Ajuntament de Barcelona. (2017, March 6). About the PEUAT. Access: http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/pla-allotjaments-turistics/en/

Barcelona en Comú. (2015a, February 18). Emergency plan for the first months in government. Access: https://barcelonaencomu.cat/sites/default/files/pla-xoc_eng.pdf

Barcelona en Comú. (2015b, April 26). Programa electoral municipales 2015. Access: https://barcelonaencomu.cat/sites/default/files/programaencomun_cast.pdf

Barcelona en Comú. (2016 March). How to Win Back the City en Comú. Guide to building a citizen municipal platform. Access: https://barcelonaencomu.cat/sites/default/files/win-the-city-guide.pdf

Barcelona en Comú. (2018, September 10). Habitatge Més que Mai. Access: https://barcelonaencomu.cat/ca/post/habitatge-mes-que-mai

Bellver, C. (2017, May 22). “Què opinen els moviments socials de Barcelona dels dos primers anys de mandat d’Ada Colau”. Crític. Access: http://www.elcritic.cat/actualitat/que-opinen-els-moviments-socials-de-barcelona-dels-dos-primers-anys-de-mandat-dada-colau-15474

Bellver, C. (2018, January 17) “Busques pis? Causes i conseqüències del ‘boom’ del preu del lloguer”. Crític. Access: http://www.elcritic.cat/reportatges/busques-pis-causes-i-consequencies-del-boom-del-preu-del-lloguer-20451

Blanco, I., Salazar, Y., ve Bianchi, I. (2017, March 15). “Transforming Barcelona’s Urban Model? Limits and potentials for radical change under a radical left government”. Centre for Urban Research on Austerity. Access: https://www.urbantransformations.ox.ac.uk/blog/2017/transforming-barcelonas-urban-model-limits-and-potentials-for-radical-change-under-a-radical-left-government/

Bookchin, D. (2018). “What is municipalism?”. Junqué, M., ve Shea-Baird, K. (Ed.). Ciudades Sin Miedo: Guía del movimiento municipalista global. Barcelona: Icaria

Castro, M. (2018). “Barcelona en Comú: The municipalist movement to sieze the institutions”. Lang, M., König, C.D., ve Regelmann, A.C. Alternatives In a World of Crisis. Global Working Group Beyond Development. Access: https://www.rosalux.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/2018/Alternatives-in-a-World-of-Crisis-Conclusions.pdf

Colau, A., ve Alemany, A. (2013). Sí que es pot! Crònica d’una petita gran victoria. Barcelona: Edicions Destino

Colau, A., ve Stobart, L. (2018, 14 Mart). Interview for book currently being prepared. London: Verso.

Corominas, M., Moreno, F., Riera, M., ve Romero M. (2016, 24 Mayıs). “Examen (crític) del Pla de xoc de Bcn en Comú”. Crític. Access: http://www.elcritic.cat/radiografies/barcelona-en-comu-avencos-socials-pero-encallats-amb-els-grans-lobbies-empresarials-9554

Della-Porta, D., Masullo, ve Portos, M.. (2015). “Del 15M a Podemos: resistencia en tiempos de recesión. Entrevista con Donatella dell Porta.” Encrucijadas. Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales, 9.

Domènech-Sampere, X. (2014). “Dos lógicas de un movimiento. Una lectura del 15M y sus libros”. Hegemonías. Crisis, movimientos de resistencia y procesos politicos (2010-2013). Madrid: Ediciones Akal

Durall, V., ve Faus, P. (2016). Film: Ada for Mayor (Alcaldessa). Nanouk Films

Errejón, I. (2011). “El 15-M como discurso hegemónico”. Encrucijadas. Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales. No.2, pp.120-145.

Fundación de los Comunes (Ed.) (2018). La crisis sigue. Elementos para un nuevo ciclo político. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños

García-Grenzner, J. (2018, April 21). “Mesa Redonda”, Transformaciones Urbanas Radicales. Encuentro Entre el Sur y el Norte Global. La Lleialtat Santsenca, Barcelona.

Gerbaudo, P (2012, December 12). “Not fearing to be liked: the majoritarianism of contemporary protest culture”. Open democracy. Erişim: https://www.opendemocracy.net/paolo-gerbaudo/not-fearing-to-be-liked-majoritarianism-of-contemporary-protest-culture

Harman, C. (1968-1969, winter). “Party and Class”. Marxists’ Internet Archive. Erişim: https://www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1968/xx/partyclass.htm

Junqué, M., ve Shea-Baird, K. (Ed.) (2018). Ciudades Sin Miedo: Guía del movimiento municipalista global. Barcelona: Icaria

Martínez, I. (2018). “La Trinchera de la Proximidad”, in Junqué, M., ve Shea-Baird, K. (Ed.). Ciudades Sin Miedo: Guía del movimiento municipalista global. Barcelona: Icaria

Observatorio Metropolitano. (2014). La apuesta municipalista: La democracia empieza por lo cercano. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños

Pérez, L. (2018). “Feminizar la política a través del Municipalismo”, in Junqué, M., ve Shea-Baird, K. (Ed.). Ciudades Sin Miedo: Guía del movimiento municipalista global. Barcelona: Icaria

Rodríguez, J., ve Stobart, L. (2017, November 29). Interview for book currently being prepared. London: Verso

Rodríguez-López, E. (2016). La política en el ocaso de la clase media: El ciclo 15M-Podemos. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños

Rubio-Pueyo, V. (2017). Municipalism in Spain. From Barcelona to Madrid, and Beyond. New York: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. Access: http://www.rosalux-nyc.org/wp-content/files_mf/rubiopueyo_eng.pdf

Shea-Baird, K. (2016, Spring). “The Disobedient City and the Stateless Nation”. ROAR Magazine. Access: https://roarmag.org/magazine/the-disobedient-city-and-the-stateless-nation/

Shea-Baird, K. (2018, May 11) “What’s it like for a social movement to take control of a city?”. The Ecologist. Access: https://theecologist.org/2018/may/11/whats-it-social-movement-take-control-city

Stobart, L. (2017, October 10) “Catalonia: Past and Future”. Jacobin. Access: https://jacobinmag.com/2017/10/catalonia-independence-franco-spain-nationalism

Stobart, L. (2018a, May 14). “The State vs People Power in Catalonia”. New Internationalist. Access: https://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2018/05/14/committees-for-the-defence-of-the-republic

Stobart, L. (2018b, June 18). “Sánchez and the Catalan crisis”. Jacobin. Access: https://jacobinmag.com/2018/06/catalan-independence-pedro-sanchez-rajoy

Stobart, L, Colau, A., ve Fachin, A.D. (2018, June 26). “The World Today With Tariq Ali – Spain: Changing of the Guard”. Telesur. Access: https://videosenglish.telesurtv.net/video/726848/the-world-today-726848/

Subirats, J., ve Rendueles, C. (2016). Los (bienes) communes. ¿Oportunidad o espejismo? Barcelona: Icaria editorial

Taibo-Arias, C. (2012). “The Spanish Indignados: a movement with two souls.” European Urban and Regional Studies. 20 (1), pp.155-158

Téllez, J., ve Stobart, L. (2017, November 29). Interview for book currently being prepared. London: Verso.

Photo Credits (in sequential order)

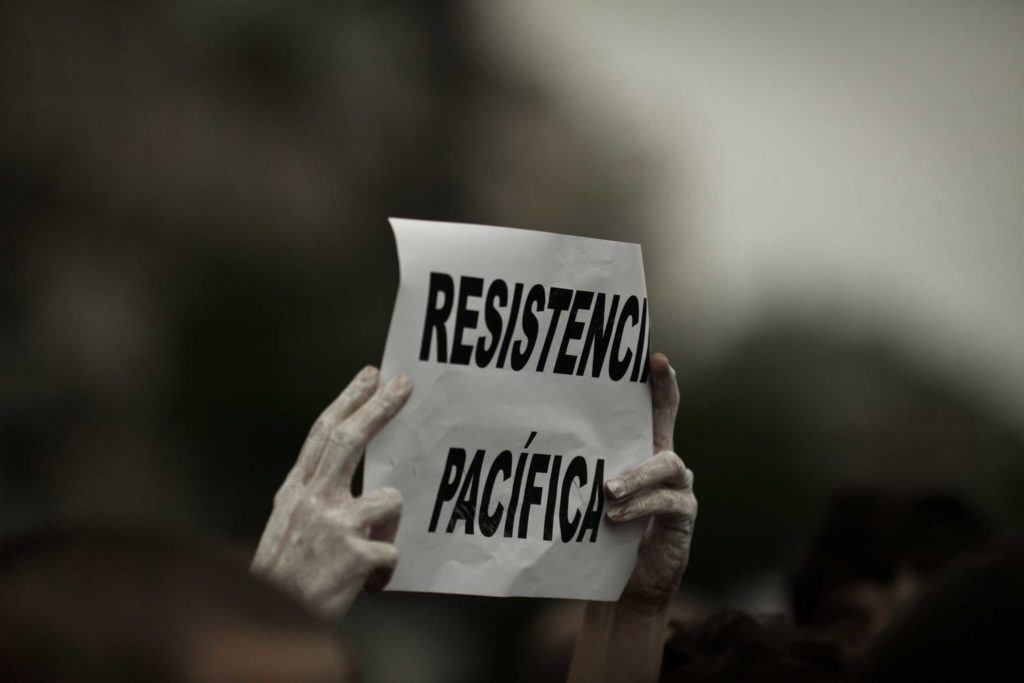

19J @ bilbao (III) ![]() by Andres Miguez

by Andres Miguez

19j @ bilbao (IV) ![]() by Andres Miguez

by Andres Miguez

29M – Vaga general ![]() by Julien Lagarde

by Julien Lagarde

Tiempos muertos ![]() by Julien Lagarde

by Julien Lagarde

Stobart is an activist in social movements in London, Barcelona, and Madrid, and is a writer and academic, specializing in Catalonia and Spain. He writes for The Guardian, Jacobin, Contexto, Viejo Topo, and New Internationalist. He lectured in political economy at Birkbeck and Richmond Universities. He has a PhD in immigration politics in Catalonia. He is currently writing on recent challenges to the status quo in Spain for Verso Books.